Continuing one of the more successful reinventions from standup comedian to stage actor, Lenny Henry stars in Fences, part of August Wilson's "Pittsburgh Cycle" of ten plays about being a black American in the 20th century, each covering a different decade. This is the 1950s' installment, where Henry plays Troy Maxson, a rubbish man who at the start of the play is lobbying his union to help make him the first black man in the city to drive the truck instead of picking up the rubbish behind it. He'll get the wished-for promotion (despite his lack of a driving licence,) but like many things in his life it won't turn out to be quite what he expects. Now in his fifties, he's haunted by the professional baseball career he never quite had, and sees his life as a series of duties he has to carry out for his family.

Troy fits into a long tradition of great American anti-heroes in theatre: Hard-working and essentially caring towards his family, he's also prone to taking his frustrations out on them, and deliberately withholds affection from his son. His harmless mythologising of his past conceals a tendency to bury uncomfortable truths - like how he actually bought the house he says he worked for.

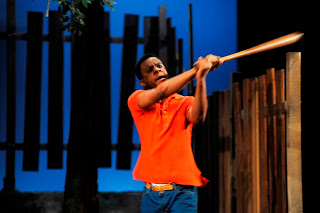

There's a powerhouse central performance from Henry as a man whose bitterness and stubbornness get in the way of his good intentions, but there's other performances worth noting here, not least of all an explosive Tanya Moodie as his wife Rose, wearily loyal but able to stand up for herself as well.

Having been disappointed in his own life and by Lyons (Peter Bankolé,) the son he had very young, Troy's determination to keep his 17-year-old son with Rose on the right path only serves to alienate him. Cory's got the opportunity to play college football but his father vetoes it, believing a black sportsman will stand no chance, just as he was sidelined in his baseball-playing days. Although, tellingly, he refuses to acknowledge Rose's alternative theory: That after serving 15 years for manslaughter, it was his age that kept Troy from glory, not the segregated baseball leagues. Stuck in the middle of this while trying to strike out as his own man, Ashley Zhangazha conveys the complex mix of emotions Cory has for his father.

Paulette Randall's production manages a couple of heart-stopping moments of tension, and although the ending is far too drawn out overall Fences comes across as both a disturbing allegory for where exactly black Americans stood in the 1950s, and an intense portrait of a desperately flawed man.

Fences by August Wilson is booking until the 14th of September at the Duchess Theatre.

Running time: 2 hours 40 minutes including interval.

No comments:

Post a Comment